Beethoven in 1804

Ludwig van Beethoven started working on his C minor symphony in 1804, right after his Erioca Symphony, but only completed it four years later. The long gestation was partly due to the interruption of his efforts on other works, including the Fourth Symphony in the summer of 1806, but probably was attributed more to his struggle itself in composing this piece. Many sketches of the ideas related to the symphony have been discovered over the years; along side his original score book, it clearly showed many rewrites and revisions the composer had gone through in order to arrive at the final shape of the Fifth as we hear today.

1. Allegro con brio

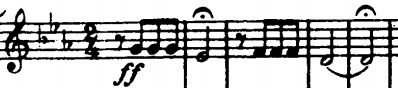

The first movement adheres to the classic sonata form. The opening motif, famous four notes with a short-short-short-long rhythmic pattern, is not only the main subject of the first movement, but undoubtedly the cornerstone of this entire symphony:

There are many interpretations on the “meaning” of this motif, which even among music scholars are not universally accepted. The notoriously publicized “fate knocking on the door” statement based stories from Beethoven’s secretary is considered made up, and there is this idea of “V for Victory” Morse Code signal in the Second World War, which to me sounds really far fetched. Yet in another theory from conductor John Eliot Gardiner, he believes the opening motifs represent a hidden radical message that expresses Beethoven’s sympathy with the ideals of French Revolution, liberty, equality and brotherhood.[1]

Regardless, it is not difficult to imagine why Beethoven put down such powerful and direct notes filled with rage, given the torment brought to him by his increasing deafness, his constant struggle of family fare, and his failure in pursuing marriage. If it was anything of “fate”, as George Grove asked, was it the fate “which at that early time he saw advancing to prevent his union with his Theresa? – to prevent his union with any woman?”[2]

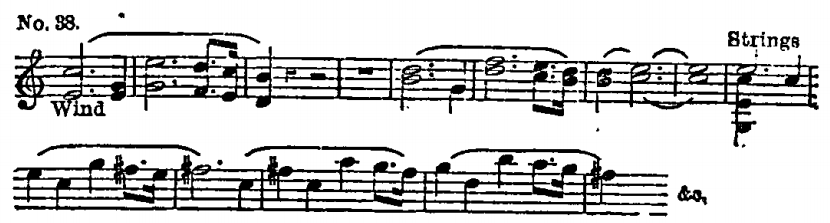

After repeating the opening phrase few times, while further elaborating the mood of impatient fury, the second subject is announced by the horn and played on the strings:

Obviously the horn is imitating the same rhythmic pattern of the opening motif, meanwhile notice how the base is also pumping that same rhythm in accompaniment.

The development section also starts with a horn call on the main motif, and then launches itself into a series of most powerful and dramatic struggle of emotions.The momentum never really stops, pushes forward all the way into the coda:

(clip takes few seconds to load)

Berlioz described this movement as “devoted to the expression of the disordered sentiments which pervade a great soul when a prey to despair”…sometimes “a frenzied delirium bursting forth in fearful cries”, and other times violence “rising again reanimated by a spark of fury”.[3] Here’s just one example of such almost desperate howling of such cries:

2. Andante con moto

The slow movement presents great contrast to the opening movement with beautiful melody and rich emotions, somewhat melancholy but overall hopeful. It is in double variation form, with two subjects going through a series variations in parallel. The first subject comes out on cellos, with pizzicato accompaniment on the base:

It is immediately followed by the winds then echoed by the strings:

Here’s the clip of the above two parts together:

The sadness in the first subject turned brighter in the second subject, which is a steady march-like tune first starting on winds:

which soon comes onto C major on trumpet:

The ensuing variations of first subject use a technique of condensing time. The first one doubles the speed to 16th note (semiquaver):

and then to 32nd note (demisemiquaver):

By the fourth time the main subject comes back, it climbs out of ascending scales and is played by the violins, back on original quaver notes but no longer gloomy in tone:

The opening motif’s shadow never fully disappears in this supposedly contrasting movement. Hear below the trumpet on the background near end of the coda:

3. Allegro (Scherzo)

The Scherzo mostly follows the traditional ternary form, with a trio in the middle, but the reprise of the first subject is quite unusual. It first starts with an introduction phrase deep down on the cello and base, giving a mysterious unease sense:

And now comes the main subject. As an often cited evidence of the unifying opening motif of this entire symphony, the subject starts again on the horn, calling out the 4-note rhythm again, and accompanied by the strings with cords on the strong beats:

After the subject repeats twice, the middle trio starts quite unusually on the double base with fast rhythm and fugal form, “resembles somewhat the gambols of a delighted elephant”[4], as Berlioz put it:

The repeat of the Scherzo subject is quite different in tone now from the first part, mostly because now it’s played almost entirely in pizzicato on strings, occasionally accompanied by the woodwinds. Grove considers “the most serious innovations” of this movement are the uninterrupted lengthy reprise of the Scherzo linking directly with the Finale, and “a fresh treatment” of its themes inside the Finale.[5]

4. Allegro

The Finale is played together with the Scherzo without interruption, as the timpani’s pounding grows louder and the strings’ tremolo rapidly intensifies, the main subject, undoubtedly one of the most uplifting and triumphant themes ever known, emerges and blasts out by the full orchestra, with the trumpet gloriously shining on the top:

Here’s how the subject comes out directly from the end of Scherzo:

There’s a second part of the main subject, equally grandiose and celebratory, led by the winds:

Following the above is a phrase that is prevalent throughout the Finale, specially fueling the development section, as if a powerful propeller pushing the emotional waves higher and higher:

Notice the bars above employ a similar rhythmic structure as the opening motif. That structure is constantly repeated and emphasized during the development.

The second subject is somewhat calmer, played by the strings:

On the original score, the exposition (85 measures long) is marked to repeat, which is rarely done on recordings. I have seen video of performances by Abbado and Rattle doing the repeat, which to be honest sounds redundant and strange. The reason, if I dare to speculate, is because our ears have become used to the uninterrupted transition from the Scherzo into the opening of Finale, and such repeat would only sound abrupt and foreign to the momentum well into the exposition already. In fact, it is the recall of the Scherzo subject during development here that allows us to re-experience that magical transition (that starts the recapitulation) again.

As the coda progresses toward the final climax, we can hear how determined Beethoven is to nail down that 4-note motif deep into people’s minds:

[1] The Secret of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Youtube.com, retrieved on 12/02/2017.

[2][5] George Grove, Beethoven and his Nine Symphonies. Novello, 1896.

[3][4] Hector Berlioz, A Critical Study of Beethoven’s Nine Symphonies with a Few Words on His Trios and Sonatas, a Criticism of Fidelio, and an Introductory Essay on Music. University of Illinois Press, 1958.