Portrait of Beethoven, by Joseph Willibrord Mähler in 1815

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 was composed in 1812, four years after his “Pastoral” symphony. What’s extraordinary about this work, in Sir George Grove’s words, is in “the originality, vivacity, power, and beauty of the thoughts, and in a certain romantic character of sudden and unexpected transition which pervades it.”[1] And one of the key characteristics that contribute to the “vivacity” and “power” here is its heavy use of rhythmic devices. To be completely honest, in the early years of listening to this piece, the endless and seemingly obsessive repetition of those rhythmic motifs throughout each movement sounded a bit annoying to me. It may be because, on a subconscious level, I was drawing contrasts between this work and all of Beethoven’s previous symphonies, which almost all carry memorable tunes and melodies, not to mention its immediate predecessor, the Pastoral symphony, of which the whole musical meaning builds on melodic motifs and phrases to express his feelings while submerging himself into the beauty of nature.

In the Seventh, however, such melodic features, if exist at all, are pushed (maybe deliberately) to the far back of Beethoven’s focus. In his conversation with Maximilian Schell, Leonard Bernstein didn’t consider the opening bars of the 2nd movement a legitimate melody at all (10 bars into the opening we hear only two notes)[2]. But, what makes this work unique (even peculiar) is it’s rhythmic features, with the general characteristics of the rhythms being incessantly forthcoming, fast and fiery. Lockwood stated that in the Seventh, “rhythmic consistency governs even more pervasively than in most of his other works…the streaming flow of rhythmic events … animates the discourse at every level and becomes a principal source of its organic unity.”[3]

1. Poco sostenuto - Vivace

The first movement seems to mimic the practice of his First, Second and Fourth symphonies, in which a significant introduction, in slower tempo, precedes the main part of the movement. Here’s the opening of the Poco sustenuto:, with its solemn and grand theme leading the introduction:

At the end of the introduction, a series of repeated E note on flute starts with a 4-bar declaration of the rhythmic pattern that will prevail the whole movement, followed by the main subject:

The second subject is equally uplifting:

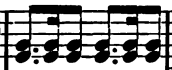

Throughout the entire movement, the dance-like dotted rhythm in 6/8 meter permeates all the sections of its Sonata form, therefore produces this unstoppable energy that propels the

Here is just one example taken out of development section:

It is considered unusual for Beethoven to write first movement of his symphony in a fast 6/8 meter, and it’s incessant rhythmic power simply makes it a bold move compared to his previous symphonies.

2. Allegretto

Similar like the first movement yet in a relatively slower tempo, this movement’s opening also starts with a steady rhythmic pattern, played first by violas and cellos:

The progression sounds grim, and barely forms a melody (as Bernstein asserted), yet we do consider it as the part A of the first subject (I-a):

When it is repeated by violin, the violas and cellos start with a counter melody to the first part, forming the second part of the subject (I-b):

That part gives somewhat a bit more color than the beginning, but together these two parts form a more drastic contrast against the brighter and smoother second subject played by solo clarinet; Grove described it as “a sudden gleam of sunshine”[4]:

As the main subject develops, part two of the main subject (I-b) grows stronger and more prominent, then Beethoven threw in a short fugue on the subject, before the full force of the orchestra repeats it and ends the movement.

3. Presto – Assai meno presto

The Scherzo brings us back to the breathless fast 3/4 meter tempo, opening with the first subject characterized by strings of descending notes:

The contrast to the Trio is so rigid and stark. As woodwinds play the sigh-like melody, the strings holds a long continuous A note, giving a sense of contradiction even within the subject itself:

That sense of contradiction grows stronger when for the second round the strings takes over the melody, and the trumpet now holds the long note.

4. Allegro con brio

The finale rides on the momentum from the Scherzo and intensifies the perpetual dance-like atmosphere. The first subject dives immediately into the whirlwind of fast flying sixteenth notes, with tympani pounding on every beat:

and an extension of it:

We also hear Beethoven’s sense of humor in the second subject:

In this entire movement, the high energy and restless force never even hesitate to charge forward, showing us “the grim, rough, humorous aspect of Beethoven, harsh and even boisterous in his outward manner and speech…and in his most playful, unconstrained, or, as he himself used to phrase it ‘unbuttoned’ state of mind.”[5]. Let’s hear how the motif from the very first bar of the finale gets turned faster and higher and thrusting full force all the way to the end:

[1][4][5] George Grove: Beethoven’s Nine Symphonies Analytical Essays. Boston, 1888.

[2] Bernstein discusses Beethoven’s 6th & 7th symphony, from Youtube.com

[3] Lewis Lockwood: Beethoven’s symphonies: An artistic Vision. Norton, 2017.