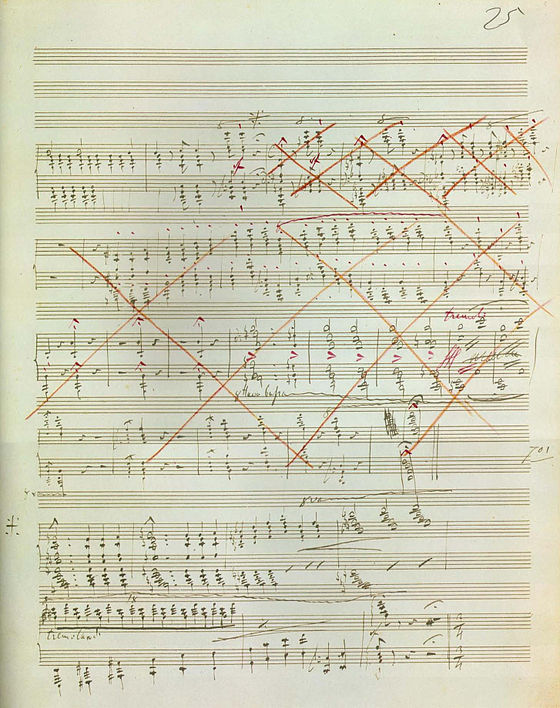

Page 25 of the original score, showing original ending crossed out.

Kenneth Hamilton provided a detailed narrative of Liszt’s Sonata in B Minor, combing through the entire score. One important point he had made was on how the themes are closely linked together through the technique of repetition.

As we all know now, the first page of Liszt’s score presents all three main themes. Hamilton pointed out that the note G, syncopated and repeating twice, starts theme one’s the descending Phrygian and gypsy scales, and later on also serves as starting note of theme 2, of which its last note also starts theme 3’s hammer-blow single-note repetitions. Therefore, each new theme begins by pivoting on the note that completed the previous one, linking otherwise highly differentiated units in a continuous flow.[1]

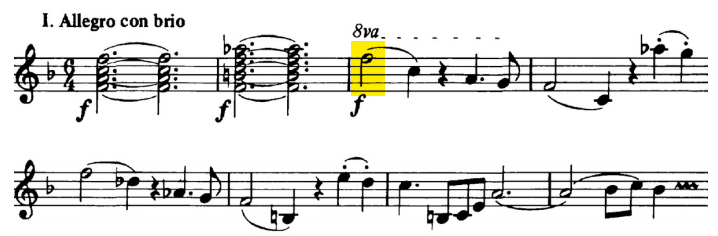

This reminds me of the same technique used by Brahms in his opening bars of Symphony No. 3, where he depicts the famous F−A♭−F motto (Frei aber froh, “Free but happy”), and the last F in this scale progression serves as the beginning of the main theme:

Evidence of such pattern is prevalent throughout the Sonata; it serves perfectly the purpose of uniting themes together, which is one important aspect of thematic transformation. To pick a few examples:

At bar 31~32, the introduction of the first subject (A), starts from the tonic B at bar 32, which is the ending note from the downward scale at the end of previous measure. Bar 30~31 calls out theme 3, with heavy accent on the hammer-blow (rinforzando) and a trill, as if the drum-roll leading to the opening scene of play (or an emotional journey in this case).

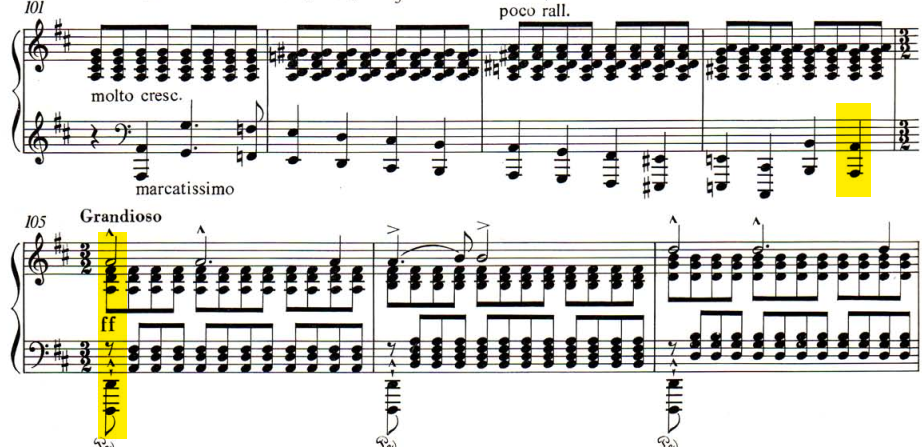

At bar 104~105, we can see how theme 1 builds up momentum by repeating itself all the way down on the lower register scales, amid the hammer-blow background on right hand, landing on A, which is the beginning of Grandioso (Subject B); the emotional build-up on minor leading to the release of major mode is just magnificent.

Bar 330~331, where the development section starts, the significant Andante sostenuto is introduced by tonally “sliding”, as Hamilton put it, the ending of theme 3, quietly echoing and fading away on lower register, into the first note of this new subject (D), which is silenced through a tie.

Another important aspect of thematic transformation is that the thematic elements go through drastic variation through various techniques (pitch, rhythmic, melodic, augmentation, diminution, inversion etc) and the original theme is much disguised in transformed new themes (while maintain the connection to its kernel). The essence of such transformation is to build contrasting characters from the original theme, thus not only allow the composer to express various emotions or tell a story, but also serves structural purposes of binding the whole work into an integral form using these derived themes. We could trace a given theme throughout the work and observe how Liszt is able to present a myriad of characters through transformation; even to untrained ears without any technical analysis, the constant shift of character and emotion are so evident and astonishing.

Take the most prevalent theme 2 (bar 8-13), its appearance on the very first page of the score is a loud forceful entrance with tension and defiance [2].

Starting from bar 123, After the grandeur of Grandoiso quiets down, the theme is almost completely disguised behind a quiet and sober tone, a mood switch towards coming subject C (another classic example of transformation through augmentation):

It’s worth noting the notes pattern at bar 124, which is first introduced here in the work and used throughout the piece later, serves as almost a “tag” on similar variations of theme 2, painting a tranquil mood rather than the theme’s original defiant tone.

Following the beautiful Cantando espressivo of subject C, the theme continues with the sweet melodic flow, now using a different rhythmic pattern, starting at bar 161 (also note the repeated quotes of the “tag”):

At bar 179, we hear passage of theme 2 that is now turned into something jumpy and unease, as it develops along side subject C yet still in the exposition section of the overall structure:

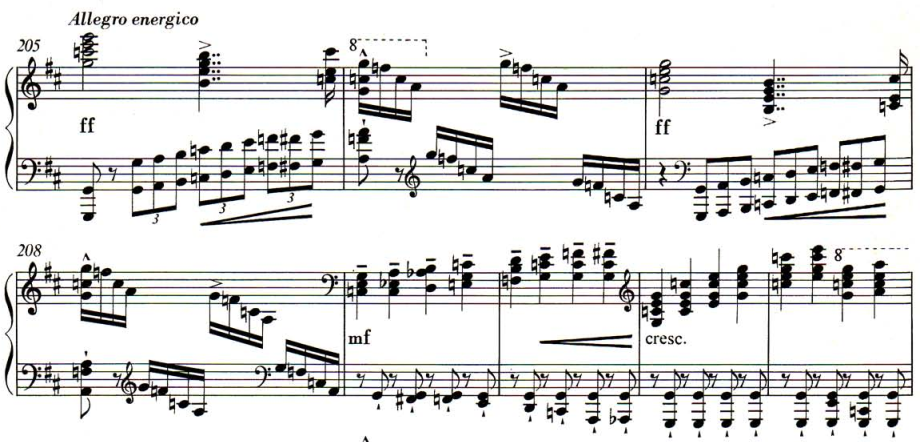

At bar 205, as the music intensifies and moving towards the climax during exposition, we hear this out pouring, passionate strong declaration of theme 2; it is later repeated (bar 523) and led the start of the recapitulation.

At bar 238, in midst of passages with the fantastic build-up of momentum leading to the climax of bar 297, we hear this melody emerged, with the outline of theme 2 clearly audible, enshrined as it is within the filigree-work of the right hand: [3]

At bar 319, as the mood calms down and approaches the Andante sostenuto, theme 2 is augmented with series of chords accompanied by murmuring theme 3 with hammering notes fading in the background.

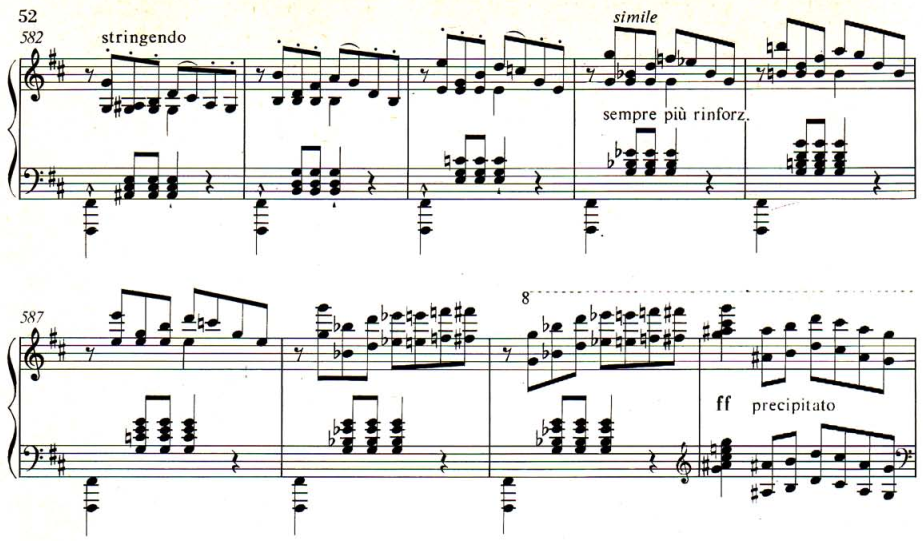

Finally at bar 582, as the recapitulation pushes toward its climax, theme 2 is now turned into a frantic rush towards a violent sneer of theme 3:

The above is merely a scan of a single theme’s transformation throughout the work. Such organic growth and complex development of all the themes (which themselves are also derived from each other; for example the 3rd subject, cantando espressivo, bar 153, is an augmented theme from the hammer-blow theme 3), bring us vast range of emotional characters in this single-movement structure. Liszt may not be the inventor of thematic transformation but he undoubtedly is the master of this important craft in the Romantic era.

[1][2] Hamilton, K: “Liszt: Sonata in B Minor” (1996), p.36, p.34

[3] Walker, A: “Reflection on Liszt”, p. 134